Extreme weather events such as the recent severe floods in New Zealand1,2, and Fiji3 are becoming increasingly frequent due to the ongoing effects of climate change in the region. These events and more underscore key lessons in infrastructure development and planning for Pacific cities and communities and the urgent need to adopt adaptation strategies that build resilience against climate change and its associated impacts. While sustainable infrastructure development is recognized as critical for economic growth and improving the livelihoods of people across the region, complex issues remain around the development and implementation of socially robust and resilient infrastructure.4

Flooding in Nadi, Fiji (February 2023).

The nexus between climate change and urbanization has contributed to the Pacific region’s vulnerability to the impacts of climate change. These issues are interlinked, as rapid urbanisation pressures are often the catalyst driving the growth of informal settlements and the creation of new climate vulnerabilities. The formation of informal settlements and infrastructure development in low-lying coastal areas often requires land reclamation, driving the destruction of mangrove forests, wetlands, and other natural habitats that provide a natural buffer against flooding and storm surges. A 2017 climate vulnerability study prepared by the World Bank in partnership with the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery estimates that FJ$9.3 billion (US$4.5 billion) over ten years is required to build Fiji’s resilience and capacity to adapt to climate change5, with measures including building more inclusive and resilient towns and cities as well as improving infrastructure services. With much of the region’s critical infrastructure – including ports, seawalls, roads and jetty’s - situated along the coast, it is important that they are well planned to enhance their resilience to climate change, maximize positive benefits and minimize negative impacts. To this end, the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP) has developed the “Good Practice Guidelines in Environmental Impact Assessment for Coastal Engineering in the Pacific” which provides guidance on implementing sustainable and resilient coastal engineering projects that take into account the impacts of climate change and the importance of protecting and restoring coastal habitats.

SPREP Coastal Engineering EIA Guidance Note

Consequently, planners across the globe are beginning to realize that traditional approaches to infrastructure development, which rely on concrete and pipes to manage stormwater, are not sufficient to withstand extreme weather events. A recent synthesis from the New Zealand Ecological Society (NZES) highlights the importance of Nature-based Solutions and water-sensitive urban design to mitigate the impacts of extreme weather events, such as flooding, in urban areas.6 Nature-based Solutions (NbS) are defined by IUCN as “actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural or modified ecosystems, that address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, simultaneously providing human well-being and biodiversity benefits”.

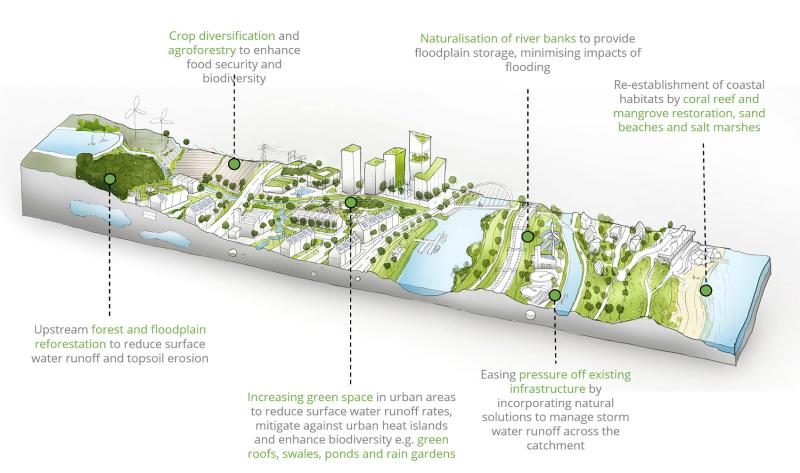

NbS encompass concepts such as green infrastructure (GI) and ecosystem-based adaptation (EbA), among others. Well implemented NbS can contribute to climate change adaptation and biodiversity conservation to support community resilience. In the Pacific where nature and indigenous and traditional knowledge deeply influence the way people live, traditional knowledge and practices related to land use, water management, and community-based conservation can inform the development of effective NbS that are culturally appropriate, socially acceptable and environmentally friendly. While NbS can play a significant role in mitigating the impacts of extreme weather events, such as flooding, the benefit goes beyond reducing flooding; they can mitigate air pollution, regulate ambient temperature, and have a raft of other benefits for human health and biodiversity. NbS can be used to compliment, substitute, or safeguard traditional gray infrastructure while delivering enhanced resilience and a series of co-benefits (e.g. supporting biodiversity, local livelihoods, and tourism and recreational opportunities). Numerous examples exist to demonstrate the efficacy of Nature-based Solutions (NbS) in addressing the infrastructure access and quality gap in a climate resilient manner. For example, rather than resorting to constructing a breakwater for coastal protection, an alternative approach would be to restore a coral reef. Similarly, rather than ignoring a dam’s surrounding watershed, a complementary approach could be to restore it to regulate water supply and reduce sedimentation. Additionally, planting or restoring mangroves around a coastal roadway can function as a safeguard against saltwater intrusion and rising sea levels.

For different landscapes there are different NbS that can be implemented to adapt to climate change hazards. Therefore, it is important to consider what are the key vulnerabilities nd harness the potential of NbS to build resilience to communities (https://infrastructure-pathways.org)

Research estimates that the median benefit of trees to megacities is about US$500m per year for each city, with large trees intercepting up to 60 percent of rainfall before it reaches the ground.6 Wetlands and forests are particularly good at absorbing water and slowing the energy of rivers, which can help to reduce the magnitude of flood impacts. However, a challenge in some parts of the Pacific region is the replacement of wetlands and natural vegetative cover with impervious surfaces and highly compacted soils, leaving little to intercept high rainfall and fast-flowing water. As such, the restoration of streams and wetlands, particularly upstream of infrastructure, is critical to improve the drainage of urban areas.

Several global initiatives are driving a rethink of how we plan modern cities by engineering alongside nature. In China, the government has launched a national initiative known as “sponge cities,” which aims to address flooding and improve the environment by implementing Integrated Urban Water Management (IUWM).7 The main concept here is that by simply reducing the number of hard surfaces and increasing the amount of absorbent land, particularly green space, the severity and frequency of flooding events can be significantly reduced. This ambitious initiative demonstrates the government’s commitment to NbS and their potential to manage water resources more effectively, create green spaces, and improve the quality of life for their residents. Closer in the region, SPREP - on behalf of the Vanuatu Government - commissioned the “Port Vila Urban greening master plan” to systematically assess and identify opportunities for Government and the community to protect and enhance the city’s’ natural assets (green infrastructure).

Sponge city concept for Nanchong CBD Urban Design (Chapman Taylor)

However, a major challenge in retrofitting at-risk communities/settlements with green infrastructure is making space for vegetation and water to flow. However, there are several possible ways to incorporate NbS and water-sensitive urban design into infrastructure development plans. For example, garden roofs, bio swales and rain gardens are nature-based solutions that can be put in much smaller places and can be particularly effective in urban areas with limited space to manage stormwater and reduce urban heat island effect through evapotranspiration. Restoring and conserving mangroves belts that support sea dykes can act as a first line of defence to reduce flood risk and erosion. Projects such as RISE's water-sensitive infrastructure in Tamavua-i-Wai community, Fiji and demonstrate that blending hard infrastructure and NbS approaches can enhance sanitation as well as manage increased flood risks and impacts of droughts far better than traditional infrastructure planning.8

A constructed wetland in Tamavua-i-Wai, Fiji capable of treating wastewater from 40 homes as it flows through plants and gravel media, before discharging cleaner water back into the environment (iTaukei Land Trust Board).

Nevertheless, implementing NbS and green infrastructure in the Pacific will require a shift in mindset and a commitment to strong leadership, support at the political and executive level, and well-planned and executed projects. Co-ordination among government agencies and stakeholders – including communities, and private landowners and developers – is essential to promote urban greening and water-sensitive urban design in infrastructure development. While NbS alone is unlikely to prevent the severe impacts of the intense rainfall and adverse climatic and weather events, incorporating NbS can significantly reduce the magnitude of flood impacts and have a multitude of other benefits for nature and communities.

References

- Davies R. New Zealand – State of Emergency as Cyclone Gabrielle Triggers Floods and Landslides – FloodList [Internet]. Floodlist. 2023 [cited 2023 Feb 24]. Available from: https://floodlist.com/australia/new-zealand-cyclone-gabrielle-floods-february-2023

- The Conversation. New Zealand’s Critical Infrastructure Is Too Important to Fail, Greater Resilience Is Urgently Needed – FloodList [Internet]. Floodlist. 2023 [cited 2023 Feb 24]. Available from: https://floodlist.com/australia/new-zealands-critical-infrastructure-is-too-important-to-fail-greater-resilience-is-urgently-needed

- Davies R. Fiji – Floods in Western Division as More Severe Weather and Coastal Flooding Expected – FloodList [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Feb 23]. Available from: https://floodlist.com/australia/fiji-floods-mid-february-2023

- Taylor N, Barbara G. Impact assessment for Pacific Island Infrastructure [Internet]. NZAIA. 2023 [cited 2023 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.nzaia.org.nz/taylorandbarbara.html

- World Bank Group. New Report Projects $4.5 billion Cost to Reduce Fiji’s Vulnerability to Climate Change. World Bank Group [Internet]. 2017 Nov 21 [cited 2023 Feb 24]; Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2017/11/10/new-report-projects-us45-billion-cost-to-reduce-fijis-vulnerability-to-climate-change

- Stanley M. Can urban greening help make cities more resilient to the ongoing impacts of extreme events? New Zealand Ecological Society [Internet]. 2023 Feb [cited 2023 Feb 24]; Available from: https://newzealandecology.org/can-urban-greening-help-make-cities-more-resilient-ongoing-impacts-extreme-events

- Gill D. Sponge City Concepts Could Be the Answer to China’s Impending Water Crisis. EarthOrg [Internet]. 2021 Aug 30 [cited 2023 Feb 23]; Available from: https://earth.org/sponge-cities-could-be-the-answer-to-impending-water-crisis-in-china/

- RISE. A Pacific first: water-sensitive infrastructure debuts in Fijian informal settlement [Internet]. Monash. 2022 [cited 2023 Feb 24]. Available from: https://www.monash.edu/rise-program/news/a-pacific-first-water-sensitive-infrastructure-debuts-in-fijian-informal-settlement